Sustainability and the Next Big Thing

In 1972, the Club of Rome predicted the sustainability problem we are facing now in the Limits to Growth book. Confronted with facts ignored for too long we need to take a hard look at where we stand and consider the possibility that the next big thing might actually be very small.

There is a story by Heinrich Böll (1917-1985) in which a businessman on vacation tries to convince a fisherman of the advantages of being industrious. The fisherman had already caught more than enough fish for the day, in fact enough for the next few days, and he’s lying on the beach, dozing in the sun. The tourist explains to him that with such excellent fishing conditions, it would be wise to go out again and catch even more, sell the excess, grow his business, and become a big player - so that one day he could retire and spend his days relaxing at the beach. To which the fisherman answered: ‘But that is exactly what I’m doing right now.’

The businessman left the scene in a pensive mood.

This story, though written in 1963, feels very topical. The Sars-CoV-2 pandemic has been globally the most disruptive event in recent history. Besides being destructive, it had another effect: it slowed us down. For a short time at the beginning of the pandemic, when we still thought it was going to go away, nearly everything deemed nonessential came to a standstill. There was panic - but also the realization that things could, in fact, be different without complete collapse. Suddenly the skies were blue, the air was clean, the roads belonged to cyclists and pedestrians. No more commuting for most of us. People had time to process what had probably been germinating in their subconscious for a while: that the life they were leading before the pandemic was not the life they wanted for themselves. This gave way to the Great Resignation.

The Great Resignation was not caused by the pandemic, only catalyzed. One thing that became apparent was that new technology had not delivered on its promise to free us from work. Machines were created to free us from repetitive and tedious work so that humans could have the leisure to do human things. But now it feels like we have even less time than ever before. How can that be?

It is a widely held belief that it is a virtue to be industrious and useful, and to delay gratification. A constant 2-3% increase in GDP and a 15-25% growth rate for businesses is considered essential. You rest, you lose. The early bird catches the worm, and the devil has work for idle hands. So if you suddenly have an extra 10 or 20 hours freed up by a machine, you could use it doing things considered to be of no economic value. Or you could work harder, much harder, leave the status quo behind, and be 10 times as productive in the same amount of time. Especially if that is what the competition is doing. 2 3

We Humans are brilliant. Just look at what we have achieved: from medical advances that keep us living healthier and longer lives, to everyday comforts that make these lives easier in every respect, be it transportation, communication, house work, or even intellectual labor. But human lives are still very short in the big picture, so it is understandable that most of us are better at tactics than at strategy. We want something and we want it now. The question of the bigger outcome later is too abstract for our brains to process.

But this is not just an individual problem. We are facing a number of threats not only to our lifestyle, but to our survival. Some of these were unforeseen, some simply ignored for too long. The awareness around climate change that has emerged in recent years has been upstaged again and again, first by the pandemic, now by the war in Ukraine. And while climate change may well be our biggest threat, it is still too abstract for most people to fully grasp, whereas the pandemic and the war feel much closer and much more personal.

However, all these threats are interconnected. Our lifestyle has resulted in an environment that made the pandemic possible, if not unavoidable, and our dependence on fossil fuels has made Germany myopic when looking at our relationship with Russia.

At the start of the pandemic lockdowns, scientists made suggestions for using this caesura as a turning point, but, unsurprisingly, we tried to get back to the status quo as quickly as possible. So, unfortunately, while the lockdowns briefly reduced greenhouse gas emissions, in the long run the pandemic hurt the climate more than it helped by creating a narrative that pitted industry and personal wealth against the welfare of the planet. 4

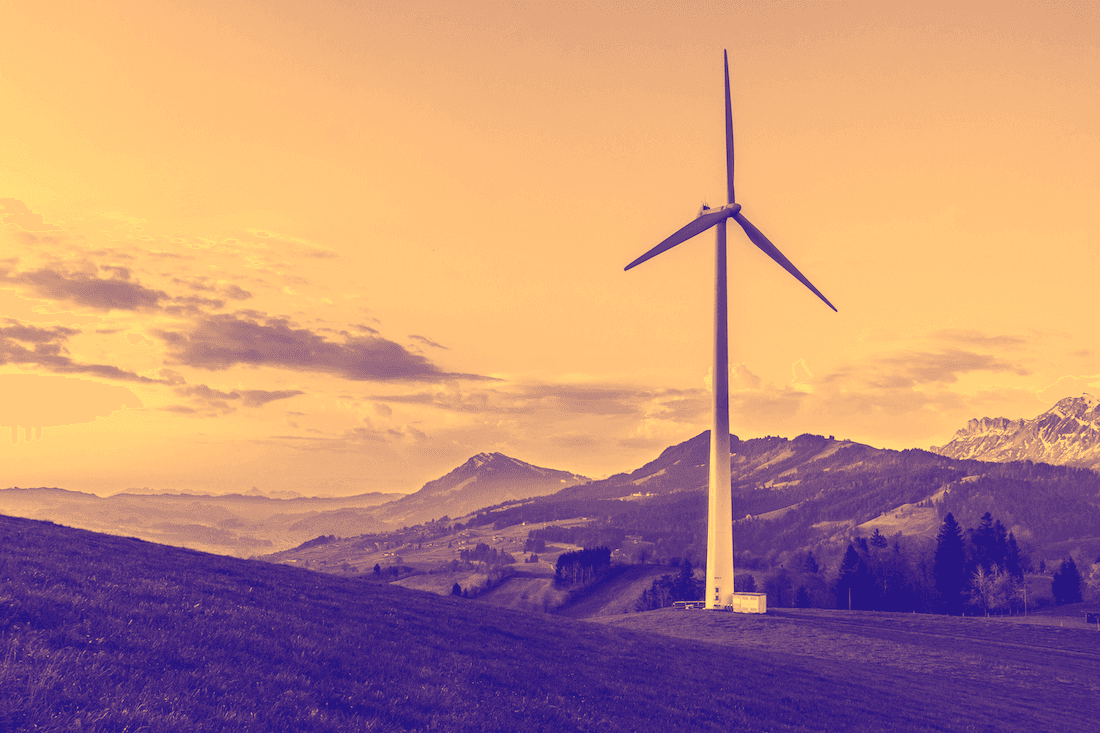

We can observe a similar tendency in the war on Ukraine and it presents us with a crucial choice: do we want to accelerate sustainable energy or do we want to go back to using more coal; do we want to be completely independent or just switch our dependence onto partners other than Putin? There would be ways to easily and effectively reduce energy consumption - for example by introducing a speed limit on German roads. The resistance to it is remarkable, considering that Germany is one of the only countries without speed limits (the others being Isle of Man and North Korea). The narrative of the kindergarten teacher and the nurse who need their cars to drive to work in the early morning hours from their homes in the countryside is used to keep fuel prices relatively low, something that benefits the wealthiest 10 percent of the population much more than the handful of nurses (a demographic that only very selectively is cause for concern), who are affected.

So we need to ask ourselves what is truly important to us: how can we survive and what does it mean to live well? The fear of losing the right to drive 300 km/h on the Autobahn is symbolic of what stands in the way of reacting to the disaster heading our way (we have already missed the opportunity to avoid it). If we cling to the idea that certain comforts are a birthright, that they must increase by 2% every year, we run into the sustainability problem already facing us. This problem is hardly new. In 1973 the movie Soylent Green, set in the year 2022, offered a pretty plausible look at what life is really going to be like very soon. So it isn’t as though we don’t know. Charlton Heston merely told us what the Club of Rome had predicted in 1972, in “Limits to Growth”.

Again, it is miraculous what we as a species have achieved; we are brilliant problem solvers. But we need to determine what the problem actually is that we are trying to solve. Maybe Soylent Green was on to something, maybe we need to reconsider the value of human life in the face of overpopulation. The Yes Men, in one of their pranks, suggested moving from fossil fuels to fuel made from people.

But let’s be serious: No one wants to revert to the days before penicillin, before washing machines, before telecommunication. Still, as we continue to grow and outgrow our resources, we might want to consider the fisherman in Böll’s story. He had everything he wanted and didn’t want more than he needed. He represents an alternative to the personality preferred in the famous marshmallow experiment, where all the children receive one marshmallow, and are given the option to eat it now or get a second one if they wait until later. According to the original study, those children able to delay gratification became financially more successful as adults. But did they have much time to spend at the beach?

It is in our nature to keep searching for improvements, to make things bigger and better, but we have reached the point where more is less. The next big thing might not be bigger. In fact, it might be smaller. If we want to ensure that life on earth remains safe for a few more generations, the next big thing needs to be more sustainable than it is now, instead of letting the ‘bigger-is-better’ paradigm devour the sustainability margin. And even though tactics are important, we need to work more on our strategy and to keep in mind our common goal. Shifting problems from one place to another in order to evade local legal restrictions will fail in the long run. Eventually everyone will be affected, with poorer countries hit soonest and hardest as climate injustice grows.

Which strategy we should pursue depends on what our goals are. In Böll’s story, both protagonists had very different goals. One sought to maximize production and profit, while the other prioritized having disposable leisure time. As time becomes a most valuable commodity, in an age where we are always reachable and always on, we may find that having one marshmallow right now is good enough. Especially since the original marshmallow experiment was not based on a representative sample of society, and a subsequent restaging found that the ability to delay gratification had a negligible effect on future success, compared to socioeconomic factors (meaning that someone from a wealthy background had a much better chance of succeeding in life than someone from a poor family, no matter how they handled their marshmallows).

The bottom line: Progress and growth are wonderful, but we may need to re-define what exactly this will look like.

Johanna ThompsonCreative Artist

Johanna ThompsonCreative Artist

Bridging Sectors: A Net-Zero Approach to Energy and Mobility with Lucy Yu

Smart Mobility Webinar #6: UK Public Transport, The Road to Recovery

The full electrification of mobility infrastructure

How different are Europe’s new energy companies from their more established competitors?

Sustainability at large energy companies – does talk translate into actions?

Are Europe’s biggest energy providers adapting their R&D efforts based on climate change?

Understanding how companies really talk about sustainability – a data- and AI-enabled experiment

Systems Thinking & Sustainability